3/3/2021

Exhibition

Nikos Fyodor Rutkowski: Personae

On view through April 30, 2022

A Closer Look:

Thursday, March 10, 5-7pm

Nikos Fyodor Rutkowski, 2, 2, 2079, 2021,

Acrylic and collaged sewing patterns on panel, 52.5 x 37 in.

Contemporary Art Matters is pleased to present Personae, a solo exhibition by Nikos Fyodor Rutkowski, opening Thursday, March 10 and on view through April 30, 2022. The exhibition features new paintings made over the past year, a time of reflection and introspection as a result of the extraordinary times in which we live.

“I’ve been drawn to masks since childhood. There was an incredible, almost mystical power that accompanied donning a mask as a kid. Even a cheap vacu-formed plastic mask of Garfield could achieve a state beyond anonymity, it allowed one to inhabit a role, to adopt a new persona. It is safe to say that masking traditions appear in a preponderance of cultures across our world, and they are usually connected to long held rites of passage, rituals of renewal, or elevated performance art forms. In America our masking traditions, like most of our traditions, align on more commercial, more watered down notions of masking.” Nikos Rutkowski

Nikos Fyodor Rutkowski, Mask #1, 2021,

Sewing patterns and acrylic on panel, 21 x 21 in.

The artist has been a collector of masks from around the world, predominantly from Africa and Southeast Asia. Through the pandemic, masks have taken on a deeper symbol for the artist. The idea of “masking up” has become ubiquitous across our planet. Protective medical facial coverings lack the transformative power of a true mask, they only have the ability to anonymize us in public.

In Protection and 2/2/2079, Rutkowski revisits the visual trope of space explorers. Many times during the pandemic the artist felt like a cosmonaut, exploring alien terrain every time he went to a grocery store or coffee shop. Protection has multiple meanings: protection in the form of the gear worn by the figure, the form of a weapon, and the form of a fetish item (the doll) that a child might carry around for security. 2/2/2079 references a snippet scrawled on the side of the painting ‘Groundhog’s Day on Mars’, a sentiment reflected in the title. For Rutkowski, much of the past two years has felt repetitive, trapped within a bubble staring out into the abyss. The eyeball form in the top right corner of the painting is a visual manifestation of Nietzche’s oft repeated quotation “…if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

Dance Into The Fire takes its name from the refrain of the Duran Duran theme song for the James Bond movie A View to a Kill. The phrasing from the song deeply embedded itself in the artist’s head as he worked on the painting because it looks like a masker dancing around a fire as part of an unknown ritual. Day of 2020 has taken on a deeper meaning after the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent protests, presenting the vision of a protestor caught in fire and smoke. Masks speak to the power of our times, images invoking the traditions of our ancestors, as well as our unsettled recent past.

Nikos Fyodor Rutkowski, Smoke and Mirrors, 2021,

Sewing patterns and acrylic on panel, 55 x 53 in.

Smoke and Mirrors is a still life, a meditation on our times, missing friends and family. This feast without guests in attendance was also about the absence of ceremony and tradition. It takes this premise farther into a presentation of ad hoc spirituality. The effigy sculptural form of a makeshift deity offers a hodgepodge of items: foodstuffs from different cultures and regions; blades that run the gamut from cutlery to weaponry; a Ukrainian Easter egg that refers to the artist’s own ethnic background. This is a wholly American god: a scene full of chunks that have softened, but not yet fully integrated into the melting pot.

The mask paintings without figures are part of an ongoing series and the artist’s working process is evident in these pieces. They are developed directly onto the canvas, intuitively, by collaging sewing patterns on the painting surface. The image emerges from the found shapes and overlapping patterns. Personae refers to all of the works in the exhibition, but this series of masks can be seen as dramatis personae- a real cast of characters.

While the pandemic has been a destabilizing and destructive force, how we perceive ourselves and those around us has been permanently altered. Tribalism, part of society for some time, has taken a firmer hold. Face masks are emblematic of this era, both here and abroad. Masks in general are a symbol of various cultures and reflect aspects shared by all in the human experience.

Nikos Fyodor Rutkowski is based in Columbus, OH where he lives with his wife and three young boys. He has received many accolades for his work, most recently a 2021 Individual Excellence Award from the Ohio Arts Council. He received his Bachelor in Fine Arts from The Columbus College of Art and Design.

Artists in the News:

Arne Svenson and

Billy Sullivan

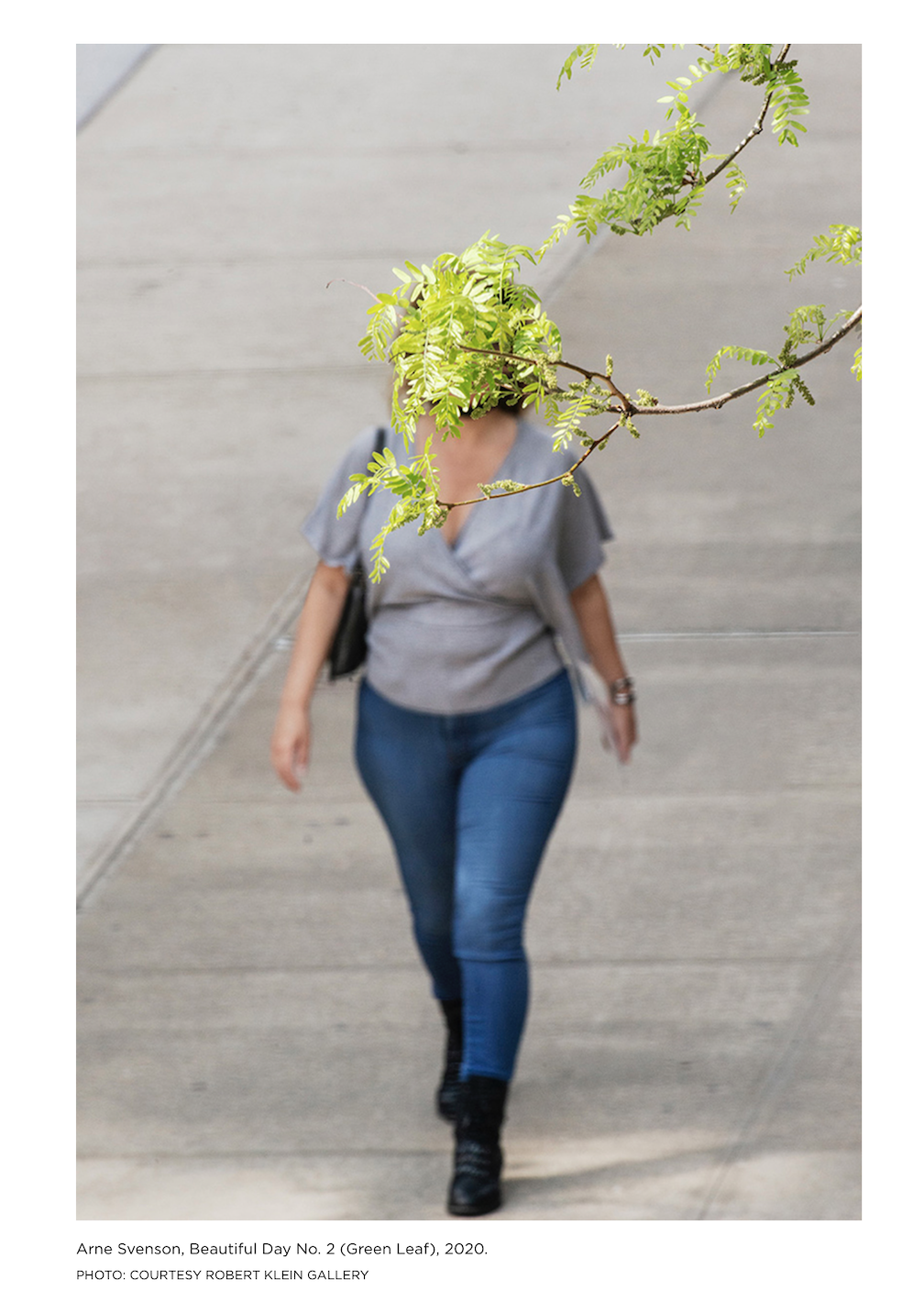

8. Arne Svenson at Robert Klein Gallery in Boston

Exploring subjects in specific series of images, photographer Arne Svenson has made voyeuristic pictures of his New York neighbors, who were unaware of being photographed through their windows until the images were exhibited; pedestrians walking in front of a white wall on a Las Vegas street, as if they were frozen in front of seamless paper in a photo studio; and people eating, drinking and daydreaming in a café opposite his Tribeca studio. During the Covid-19 lockdown, Svenson made the most of his time indoors by aiming his long lens at passersby on the streets below his New York apartment windows. Capturing candid shots of people venturing out, he found the studio of the street to be a place filled with wonders once again, and—through a bit of ingenious cropping—the 38 pictures in the exhibition “A Beautiful Day” reveal the beauty and resilience of humanity, even in the worst of times. Through March 19

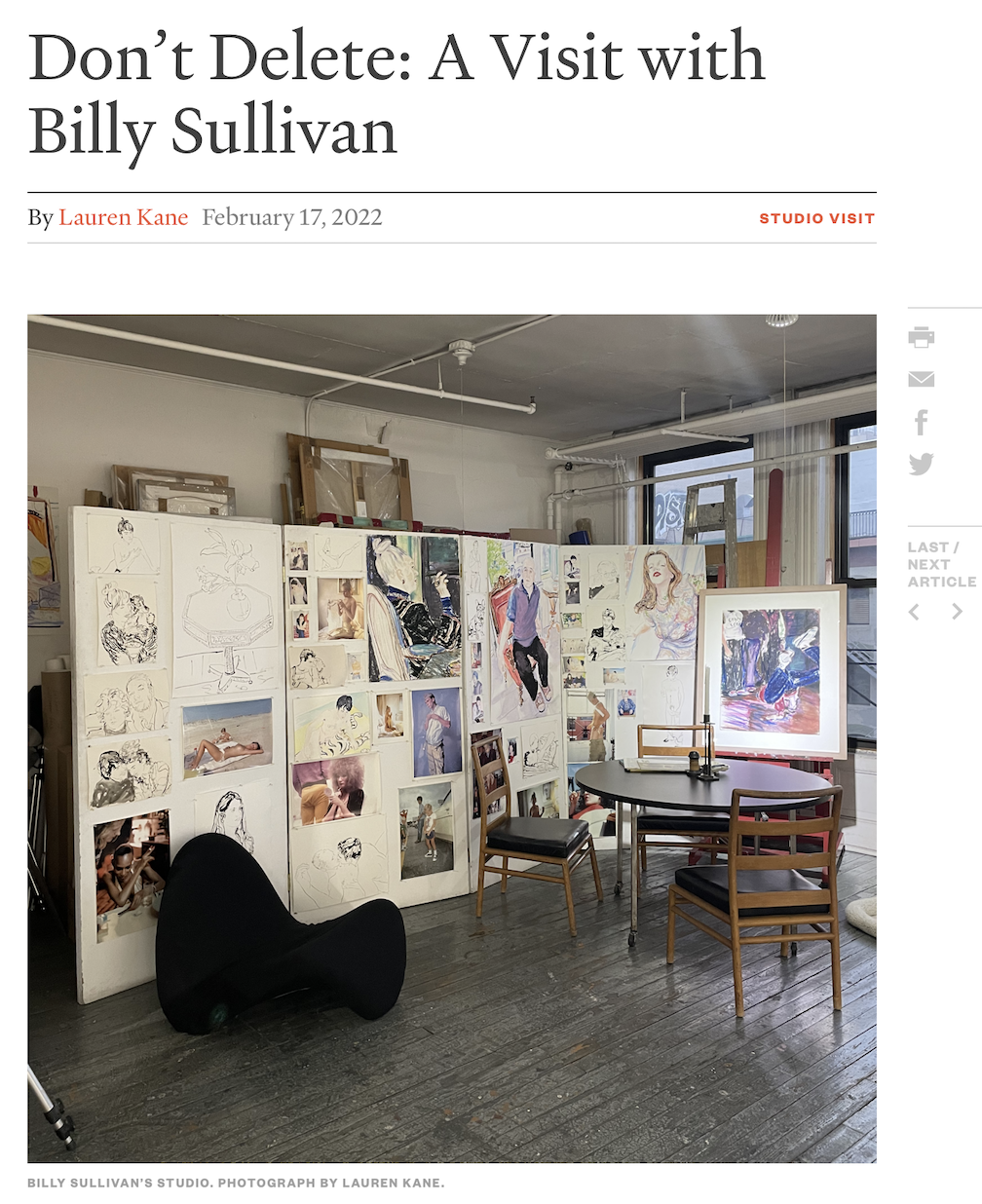

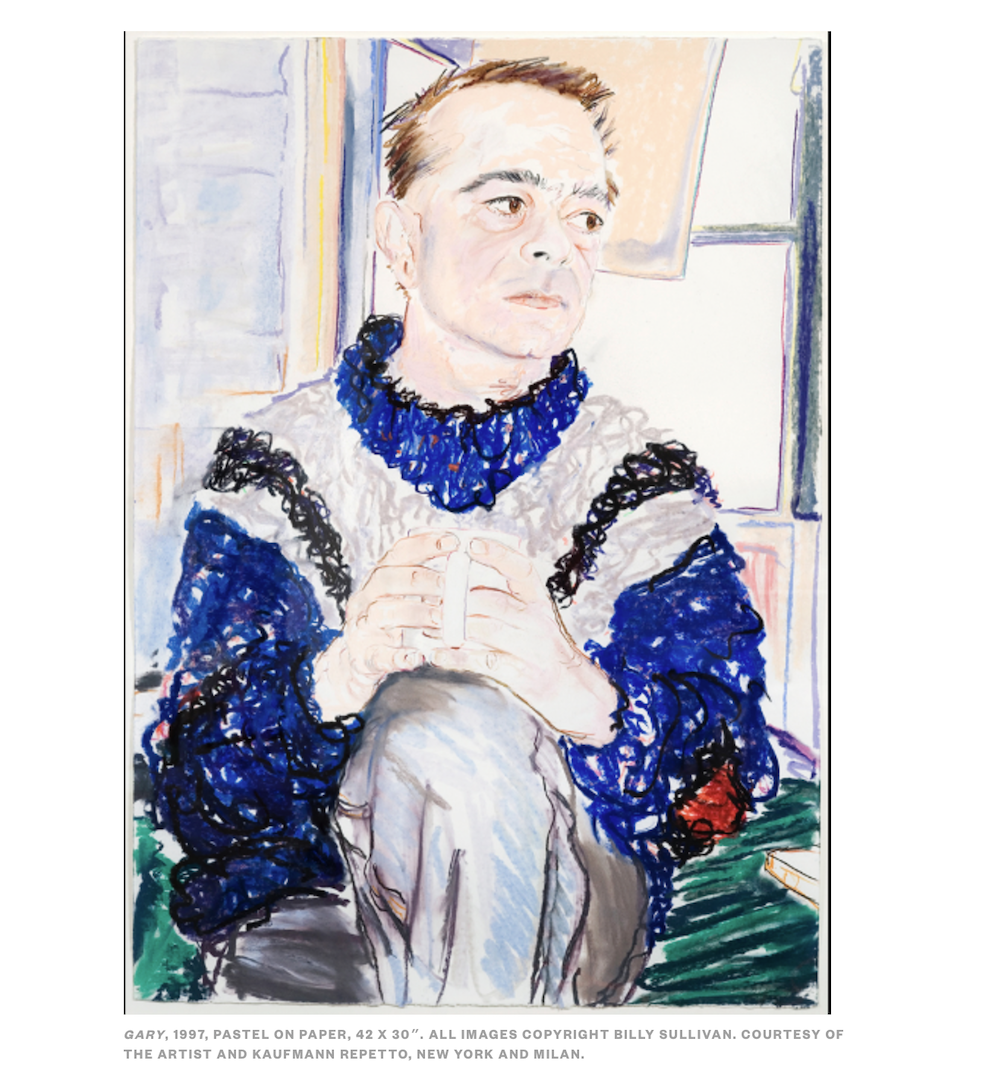

Billy Sullivan’s studio, a fifth-floor walk-up on the Bowery, has a comfortable, elegant dishevelment. Hanging all around the space are some of the brightly colored figurative drawings and paintings he has been making since the seventies: portraits of his friends, lovers, and other long-term muses, rendered in loose, dynamic brushstrokes and from close, pointedly subjective angles. A still life of a bouquet and two coffee cups is an outlier among the faces. Near a work in progress on the wall is a table with a color-coded array of pastels, each wrapped in its paper label (mostly the artisan Diane Townsend, with a few older sticks from the French brand Sennelier); a metal cart bears tubes of oil paint, and carousels of slides are tucked away on low shelves. Tacked up on a set of folding screens is a display of Sullivan’s photographs and sketches, and next to that is a burgundy chaise longue adorned with a faux animal pelt. When I visited on an overcast afternoon in December, Sullivan had set out a bowl with grapes and a fig on the kitchen island, where he pulled an espresso for himself and poured a glass of water for me.

I had brought along a copy of Gary Indiana’s 2003 novel Do Everything in the Dark, a contemporary answer to George Eliot’s Middlemarch, which follows a tight-knit group of artistic New Yorkers who, over the years, have either realized or surrendered their potential for happiness. As Indiana explains in an Art of Fiction interview in the Winter 2021 issue of the Review, the novel began as a series of vignettes intended to accompany Sullivan’s paintings of people they both knew in the “downtown” scene. We looked through images together, and Sullivan told me some of the stories behind them. That milieu—Cookie Mueller was a part of it, as was the FUN Gallery founder Patti Astor—flourished for only a few years, from the seventies through the tragic onset of the AIDS epidemic, and is often fetishized, much to Indiana’s irritation. The very word downtown carries a whiff of romance, especially when spoken by those too young to have known an era when you could live in Lower Manhattan on next to nothing. “There was a lot more free time,” as Sullivan puts it, and to be an artist essentially meant that “you got respect from your peers and you hung out with people you really liked.”

Sullivan is mild-mannered and considers himself a wallflower, an observer. While we sat and talked, he kept lifting his phone to take quick images of me as I fidgeted, recrossing my legs or tying up my hair. His photographs—he calls them his sketchbooks—have a loose, spontaneous quality, conveying an intimacy that invites the viewer in. The second time I referred to them as “candid,” he corrected me. For Sullivan, there is no distinction to be made between a candid photograph and any other kind.

Gary was always around at night. I was interested in the way he wrote—dynamite art criticism. His writing was sort of like poetry. We ran pretty much in the same places at the same time. I’d see him when I went to the barber, and we’d go to the same restaurants, too, like Mickey Ruskin’s at One U. Places where you could go and get food and it didn’t cost anything. One U took the place of the back of Max’s Kansas City, where it first started for me. You would go to One U at around ten o’clock. Everyone would show up there, and you would play around. And then there was the Mudd Club. Gary would go. It was what you did at night. And it would be whoever was interesting. We never thought of it as the underground. It was just the world, and everyone was hanging out. You wouldn’t call somebody and say, “Are you going?” You would just show up.

You didn’t want to use the phone. There was all this paranoia because we were anti-war, we were anti all these things. And the older people, like Brice Marden and those guys, they would be really frightened of the FBI.

Gary became a muse for a while. We became friends over a long period of time, and it was always interesting—something was always going crazy in his life, and you got to hear that. We would have these long telephone conversations, kind of piecing together what happened the night before. In the morning you would check in and see when you left somewhere and what you did. It used to be a whole part of my life was, the next day, trying to figure out what exactly happened.